Meat Eating Is in Alignment With Human Evolution

And Why Vegans Are Simply Wrong About It.

The ideological veganism goes beyond diet and lifestyle wisdom to a sort of counterfactual crusade. I call it veganism as a religion. This crowd has faith that not only is meat-eating bad for humans, but that it’s always been bad for humans—that we were never meant to eat animal products at all, and that our teeth, facial structure and digestive systems are proof of that.

But sorry, that's just not true. As a new study in Nature shows, not only is the processing and consumption of meat innate in humans, but it's perfectly possible that without an early diet that included ample amounts of animal protein, we wouldn't have become humans in the first place - at least not the modern, linguistically gifted and intelligent people we are.

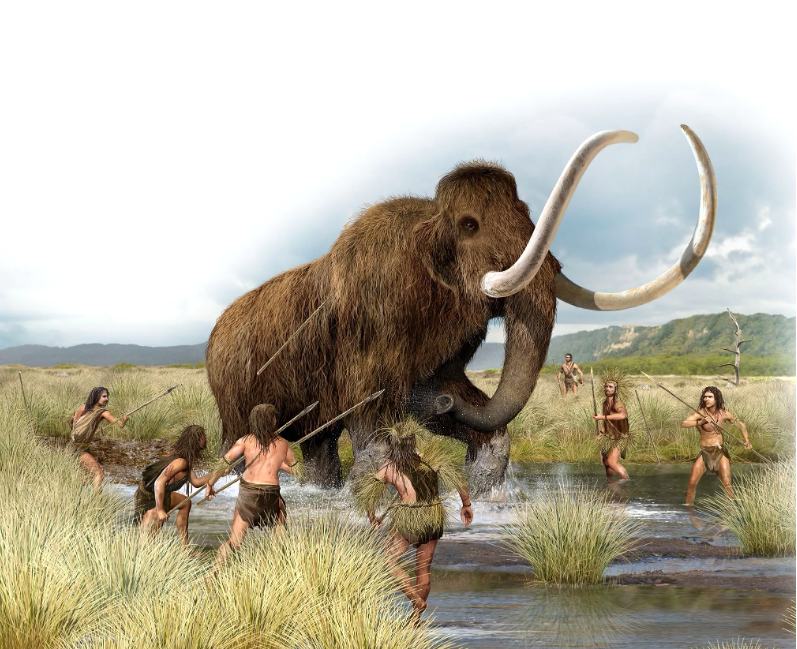

About 2.6 million years ago, meat first became a significant part of the prehuman diet. Being a herbivore was easy - fruits and vegetables don't run away, after all. But they're not particularly high in calories, either.

A better alternative was the so-called underground storage organs (OSU’s), root products such as beets, sweet potatoes and potatoes. They contain more nutrients, but they are not particularly tasty, at least not raw. And are difficult to chew. According to Harvard University evolutionary biologists Katherine Zink and Daniel Lieberman, authors of the Nature paper, ancient humans who ate enough root foods to stay alive would have had to undergo up to 15 million "chewing cycles" per year.

That's where flesh came in - running and scurrying to save the day. Prey that has been killed and then prepared either by cutting, pounding, or chopping provides a much higher calorie meal that requires much less chewing than root vegetables, increasing the overall nutrient content. (Cooking, which would have made things even easier, only came into fashion 500,000 years ago).

To find out how much energy primitive humans saved by eating processed animal proteins, Zink and Lieberman recruited 24 modern humans and fed them samples of three types of OSUs (sweet potatoes, carrots, and beets) and one type of meat (goat, raw, but examined to ensure that no pathogens are present). They then used electromyography sensors to measure how much energy the head and jaw muscles had to expend to chew and swallow the samples, either whole or prepared in one of the three ancient ways.

They found that, on average, processed meat requires 39% to 46% less force to chew and swallow than processed roots. Cutting meat worked best because not only is it particularly easy to chew, but it also reduces the size of the individual particles when swallowed, making them more digestible. For OSUs, pounding was best - a happy fact that would one day lead to mashed potatoes. Overall, Zink and Lieberman concluded, a diet that was one-third animal protein and two-thirds OSU would have saved early humans about two million chews per year - a 13% reduction - a corresponding saving Time and calories just to scarf down dinner.

There were reasons for this that went beyond the fact that our ancestors had a few extra free hours in the day. A brain is a very nutritious organ, and if you want to grow a large brain, eating at least some meat will give you far more calories, protein, saturated fat, and cholesterol, for which our brain is hungry for, with far less effort were just more than ideal. Add to that the fact that animal muscles, eaten directly from the carcass, require a lot of ripping and tearing - which requires large, sharp teeth and a powerful bite - and that once we learned to process our meat, we were able to save some of that , by developing smaller teeth and a less pronounced and muscular jaw. This, in turn, may have led to other changes to the skull and neck that favored a larger brain, better thermoregulation, and more advanced speech organs.

“Whatever selection pressures favored these shifts, they would not have been possible without increased meat consumption combined with food processing technology.” the researchers wrote.